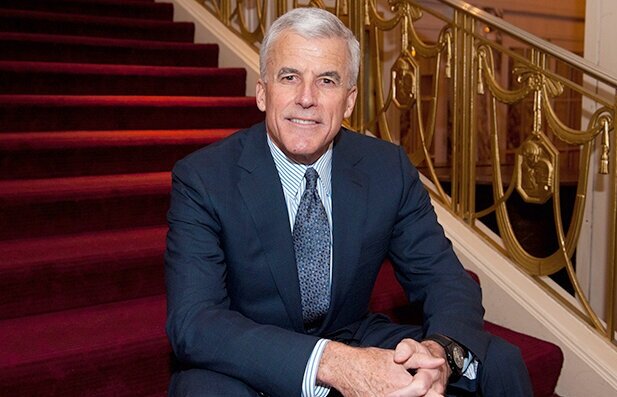

Official Caddying Story: Bill Doyle

Bill Doyle, Georgetown University

The longtime CEO of PotashCorp (now Nutrien), Bill Doyle led the Canadian fertilizer conglomerate when it helped produce half of the world’s food. He now serves as the chairman of Georgetown University’s board of directors, where he and his wife, Kathy, have also established the Doyle Program for Engaging Difference. He supports other education-related causes like the Evans Scholars Foundation, the Big Shoulders Fund, and his other alma mater, Loyola Academy. But long before he became one of Harvard Business Review’s top-rated CEOs, Bill got his start as a caddie, along Chicago’s north shore. In his Official Caddying Story, he shares many insights about how golf has shaped his life, including stories about Arnold Palmer, Bill Murray, Martin Sheen, and his 50-year friendship with Fred Blesi.

At which golf course did you first caddie and how old were you when you started?

I started caddying at Bob O’Link when I was 10 years old. I ended up caddying there for 12 straight years, all the way through college graduation. It was the perfect place for me, like another home. I prided myself on knowing every blade of grass. A lot of fun experiences, I was lucky to have worked there.

Why were you compelled to become a caddie?

Needed the money, there was no other source. We didn’t have allowances growing up. We had to work. We also knew that we had to pay for our schooling, so we figured that we'd better get at it from a young age. I thought about a paper route but heard you could make more money caddying.

At 12, my older brother had started caddying at Bob O and brought me over. You had to be 13 years old, so he instructed me to say that I was no matter how many times I was asked. Now keep in mind, I was a little squirt. Short and skinny, I weighed 70 pounds max, at least 45 pounds less than my brother. Upon meeting me, the caddie master said, “You’re not 13, sonny.” I held firm. He stared at me and told me to go sit down in the caddie yard.

I sat in the yard for an entire week before ever getting a loop! I’d ride my bike over at 7AM and wait there until 6PM. The only reason that I ever got a chance to caddie was because it was a Sunday, and there wasn’t another kid in the shack.

Take us through your first day on the job, who was your first loop?

For that first loop, they called me up and asked if I could even carry the bag. I tried putting it on my shoulder, and sure enough, the bottom of the bag hit the ground. So they tied some knots in the strap and told me to use my back, kind of bending over. The most important thing that I’d heard in the yard was to never let your player beat you to the ball. With that in mind, I took off running from the first tee after all of the players had hit. It must have been hysterical since they all started laughing at me when I was about 100 yards in front. After the round, I was just exhausted but looking forward to collecting my fee, which was supposed to be three bucks. Bob O’Link was known to pay well, and that was the going rate. The guy takes out one of those rubber change purses that looks like a football. He pulled out a quarter and pressed it into my palm telling me not to spend it all in one place. He was a dentist and one of the cheapest loops, as I came to find out. It was a good start.

The caddie yard proved to be so much fun. Waiting in there for 10-12 hours per day early on, I just soaked it up. Sure, you had to steer clear of certain guys who may get a kick out of punching you in the arm, but there was so much to learn. It was a different culture; it was perfect for me at such a young age. You learned skills like cards or pitching pennies but also about bigger topics like sex education from pro caddies who’d bring in adult magazines. The pro caddies, with names like Cucamonga Pete or Jack The Ripper, spent most of their money on booze and often smelled like it. But you learned so much about life. When I did finally turn 13, my dad tried to sit me down for the “birds and the bees” talk. I gently said, “You can skip this. I already know. I’ve known for years.”

What was the biggest mistake that you made during your caddying career?

My biggest mistake caddying was especially painful since it happened when I was on the bag for Arnold Palmer. It happened the second time that I got to caddie for him at Bob O’Link in front of a huge crowd, and he was just such an incredibly kind person. He’d show up and say, “Hey Bill, how are you doing? How are those Jesuits treating you?” I remember thinking how the hell does he not only remember my name but even where I attend high school. I even asked others if they’d tipped him off but, no, he was the genuine article. He had a great memory and really cared about people. He was a real man’s man but still very kind.

We were on the 12th hole, a par 3 that was 195 yards. That day, it was playing dead into the wind, and the pin was all the way back. It was really gusting, probably a two club wind. He had a fabulous round going so far, and he’d ask me what club to hit since we’d been out together before. He knew that I knew the greens and how to caddie, so there was some trust established. It was 195 yards, but I told him it’s got to be playing 220. He said, “I can get a 3 iron there.” I said, “I think you’ve got to hit the 2. It’s really gusting, with the pin all the way back.” He steps up and smokes a 2-iron right at the flag. It flew the green, leaving him short-sided coming back and chipping down hill! He takes his only bogey of the day. I was devastated. Walking to the next tee, I said, “Mr. Palmer, I’m so sorry. I thought the wind would knock that down.” He put his arm around me and said, “Hey, don’t think that way for a minute!” Despite that lone bogey, he shot 66 that day. It was the biggest mistake that I made caddying for sure.

If there was a silver lining, however, it surfaced many years later when I got to play with Lorena Ochoa in the Canadian Open pro-am. We had a fabulous time together and instantly became friends. She’s such an incredibly kind and gracious person but had yet to meet Arnold Palmer at that point in her career. I was able to tell her, based on first hand experience, that she and The King were cut from the same cloth.

What did you most enjoy about caddying?

Golf is the greatest game ever. You never have the same shot twice. It’s a fabulous way to learn about people, totally character revealing. You can see if someone is honest. You can see if they have a sense of humor, can control their temper, or if they’re humble. You can see if they have class. Money and class have nothing to do with each other; you can have a billion dollars and have no class or no money but all the class in the world.

When we were looking to take over another company or do a big deal, I’d ask to play golf with their CEO. I wanted to learn if I could trust the person.

Tell us about some of the people for whom you caddied, did any of them contribute to your career in a meaningful way?

I got my first “real” job through caddying from a guy named Fred Blesi. He’s still a very dear friend. We first met in 1970 when I saw him play in a tournament, while caddying for the opposite team. There was a playoff, and the caddie for one of the teams had already gone home, so I stepped in and caddied for them for a single hole en route to their victory. Even though they beat Fred’s team, he shot a two under 70, and I just admired him. I started caddying for him, and we became great friends. When I got older, he had me come work for International Minerals and Chemicals (IMC) as a sales trainee. I didn’t end up working for him until the end of my time at the company but later brought him on to my board of directors at Potash. It’s a big circle of life. He’s been a mentor to me and a wonderful friend. We’ve known each other for 50 years and are actually having a virtual cocktail party pretty soon here during the pandemic. He’s made a really big difference in my life and is just a really good guy.

What was the biggest lesson that you learned from caddying that helped you succeed as you progressed in life?

There are so many like discipline and street smarts. But a big lesson was to show up to work every day and do it with gusto and joy. Have a fire in your belly, a hunger to do it the best that you can. That has stayed with me ever since I started caddying, and I never thought about work as work. I’d get there at 7 in the morning and stay until 7 at night. All of the sudden, it’s 41 years later, and I’m retiring. It just went by so fast. But when customers would come see people in our offices having a good time, hearing them laugh, they wanted to do business with us. If you’re not happy, go do something else. Life is just too short.

Another lesson was to make hay while the sun was shining. If you can go, you go. I once caddied 63 holes in one day. Walking. When there is an opportunity to work and contribute, you do it, even if it isn’t glamorous. In addition to caddying, I’d clean the locker room, showers, and toilets. Like during the member-guest, the Hullabaloo, they’d need extra help, so I’d go in after caddying and work while the players were having cocktails. People noticed little things like that and wanted me to caddie for them. I went on the road with members in tournaments and later had an appointment book. Especially from when I was 18-22 years old, members would call our house and tell me when they were playing, so I could loop for them. My mom would help field calls, and write it all down. The caddie master didn’t like that, members calling directly, since he liked to shake down the members trying to get a tip. But he only interfered one time before a member put him in his place.

Another lesson and maybe the most important is about human skills, how to communicate and relate to people. A good caddie is also a coach, even a psychiatrist at times since some people go crazy out there. So in addition to the green reading and knowing yardages, you learn how to connect with people. We see boards messing this up all the time when they’re looking for a CEO; the candidate may have a great resume but doesn’t know how to take care of people. You have to have empathy and understand what they go through every day. It’s not just about giving them a paycheck. You have to love them and appreciate them. If they know you care, that you really care, you can move mountains.

Can you tell us a bit about your unique relationship with the Evans Scholars Foundation?

It actually dates back to 1965. It was on a Sunday when Bob O would get incredibly quiet in the afternoon after the priests had played. You could shoot a gun, and no one would notice. I had already caddied 18 holes, and the caddie master said, “Hey Doyle, stick around, I’ve got a twosome for you.” It turned out to be Chick Evans and Gene Sarazen. Gene was a little tiny guy, wearing plus fours with brown and white socks. He played Wilson Staff clubs. It was a quick 18, and Chick beat Gene. But I tell you, Gene could really smack that persimmon driver.

To this day, that experience inspired me to support the Evans Scholars Foundation. I would have loved to have earned a scholarship back then, but we were just a notch above being poor enough, even though we weren’t rich by any standard. I had the grades but didn’t qualify for the needs side of it. Now, thanks to Mike Keiser, we’ve gotten involved as a Match Play Challenge partner. I also try to mentor young caddies and help them apply for the Evans. It’s a great organization, and Mike Keiser is just unbelievable. He is so generous, humble, and really a great leader.

If you could nominate one former caddie who went on to enjoy success, whose Official Caddying Story would you like to hear?

I’d have to go with a high school classmate of mine, Bill Murray. He caddied at Indian Hill Club in Winnetka. We’ve been pals since then, and he’d be a great interview, funny as hell. He’s really a good guy. A lot of people think he’s a goofball and he is! But I’ll say that we had our 50th reunion a couple of years ago, and he performed with the same two guys from back then, their trio. And although the staff started to film with their phones, we didn’t think anything of him because we’ve known him since he was 14. He’s just the same guy, a good person and tons of fun.

Another interesting one, you may also want to talk to Martin Sheen. We had dinner together years ago with Magic Johnson, who is just an incredible man, at an event for the nonprofit Free The Children. At the dinner, Martin and I got to talking about how we both grew up caddying. He went on to describe how he actually led a unionization effort among the caddies in the yard. He ultimately got fired, and there was no union. Magic just sat there laughing and shaking his head.